James loved southwestern Montana better than any other place on the frontier. Nearly twenty years had passed since his first expedition with old Jim Bridger, but he had returned time and time again during those years. It's no wonder that he eventually chose Ruby Valley as his permanent home.

He loved to recount his Montana adventures and describe the pristine wonders of nature that few white men had ever seen. Memories of his first visit to the region were still vivid in his mind when he described them to William Wheeler in 1879:

…wonderful spouting springs at the head of the Madison and…what have of late years become so famous as the Upper and Lower Geyser Basin, the Upper and Lower Falls…and the Mammoth Hot Spring…Here we camped several days to enjoy the baths and to recuperate our animals… We made winter camp at the mouth of the Big Horn, where we had a big trade with the Crow and Sioux Indians. The next spring we returned with our furs and robes.(1)

As early as 1850 James went on trading expeditions up the Snake River, and as far as the Bitter Root or St. Mary's River among the Flathead Indians in Missoula County. He camped at Alder Gulch on the very sight where rich gold discoveries were made twelve years later, discoveries that led to one of the largest gold booms in history. “Not once did he have an idea of the great gold harvest that lay beneath him, but he saw only the beautiful and luxuriant furs and robes of the beaver, which he accumulated year after year and sent to St. Louis by way of Fort Bridger.”(2)

James made many such trading trips to Montana in the years preceding the gold rush. He entered the fertile Ruby Valley with a party of five men and packhorses in the fall of 1857, and traded with the Indians. They camped at the mouth of Daylight Gulch near Virginia City, where they met a trapper named Robert Dempsey. James went down into the Yellowstone region and traded blankets for furs with the Indians. When he returned to the valley, the snow was so deep that he was compelled to spend the winter at Dempsey’s camp and to postpone his return to Utah until spring. There was no forage for the stock, and they had to cut cottonwood boughs as feed for the mules…that was all the feed those poor animals had to live on through the long winter. The hardship and privations of that winter (1857-58) forged a life-long friendship between James and Robert Dempsey. (Dempsey and his Indian wife, who was adept in the white woman’s manner of dress and housekeeping, became good friends of James and Maria when they later moved to Sheridan.)(3)

In spring 1863, during his second expedition from Utah to the Bannack gold mines, James headed northeast to Fort Benton, a trading post on the upper Missouri River, to trade with the Indians.(4) While he was there, he purchased the sawmill machinery that was used to cut the lumber for the fort, loaded it in his wagon, and started back to Alder Gulch. When he was one day out from Fort Benton, the Indians stole his mules.(5) Refusing to accept his misfortune, yet not wanting to antagonize the culprits, he came up with a solution. He went back to Fort Benton, purchased five gallons of whiskey, and traded it to the Indians for his stolen mules. Upon his return to Alder Gulch in October he met Joseph C. Walker, who had recently settled in Montana. The two men (along with Walker’s brother and cousin) went into business and constructed a sawmill on a creek near Sheridan that became known as Mill Creek.(6)

It took twelve mules to run the new mill, plus a crew of twelve men. The fee charged for the unfinished lumber was twenty-five cents per foot. (Profits in that first year were enough that Joseph Walker agreed to pay off James’ long overdue debt ($500 for goods on credit) to the Walker brothers of Salt Lake City.) The mill crew worked hard all day, but during those long winter evenings, with nothing to read, they passed the time sitting around the fire telling stories. Five members of the crew were James’ acquaintances from Utah, so most often the conversation turned to berating the Mormons, specifically Brigham Young. James, at one time, had a cordial personal relationship with Brigham Young, but later, especially after his disaffection from the Church, James seemed bent on knocking the revered prophet down a notch or two.

|

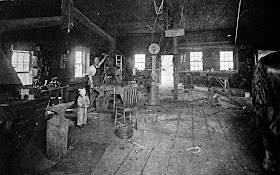

| Possible site of Gemmell's sawmill in Brandon, Montana, just a few miles east of Sheridan Photo by Bary Gammell |

|

| Brandon is located on Mill Creek just east of Sheridan |

It took twelve mules to run the new mill, plus a crew of twelve men. The fee charged for the unfinished lumber was twenty-five cents per foot. (Profits in that first year were enough that Joseph Walker agreed to pay off James’ long overdue debt ($500 for goods on credit) to the Walker brothers of Salt Lake City.) The mill crew worked hard all day, but during those long winter evenings, with nothing to read, they passed the time sitting around the fire telling stories. Five members of the crew were James’ acquaintances from Utah, so most often the conversation turned to berating the Mormons, specifically Brigham Young. James, at one time, had a cordial personal relationship with Brigham Young, but later, especially after his disaffection from the Church, James seemed bent on knocking the revered prophet down a notch or two.

Years later Walker recorded what he could remember of “the acts of the Mormons during those early years” as told to the crew by Gemmell during the long evenings at their camp on Mill Creek (twenty five miles from Virginia City, in the winter of 1863-4.) Like most mountain men, James surely had developed the gift of gab, for as Walker declared, “I have penned but a tithe of the history he [James] gave.” According to Joseph Walker, James told the crew how he made the decision to come to Alder Gulch. Two of the few confidential friends that he had left among the Mormons seemed to think that

…it wasn’t safe for him to sleep in his house [because Brigham was "down on him"]...[James] said that he spent the days with his families, and hid and slept in the brush at night, but he said he could not make a living for two families and live that way. So he got some Indian goods from the three Walker brothers [not Joseph C. Walker] on credit and with two old wagons and some Spanish mules he struck out north in the early spring of 1863 coming up through Bannack…(7)

Although Joseph Walker’s business partnership with James lasted only a year, he retained fond memories of those days, and recorded this final tribute:

…during the year Mr. Gemmell was associated in partnership with my brother A. M. Hardenbrook and myself, no partnership could have been more agreeable. Many years ago Mr. Gemmell went to his reward. Peace to his ashes. He had worked upon the treadmill of life enough. His body was interned on Mill Creek about eight miles below our winter camp of 1863-4.(8)

Walker and Gemmell saw each other for the last time in fall 1865 at Virginia City, not long after James had moved his family to nearby Ruby Valley. At that reunion, James was eager to tell Walker about his long conversation with General Thomas Francis Meagher (pronounced "Mahr"), newly appointed acting governor of Montana Territory, who had just arrived in Virginia City, the territory’s new capital. James reported that he and Meagher chatted for hours, comparing notes about the experiences they had in common. Both of these men had led very colorful lives, both had been prisoners in the British penal colony at Van Diemen’s Land, both had escaped on American whaling vessels, and both had made a home in Montana that same year.(9) Meagher, a Union officer in the Civil War, was born in Ireland. As a young leader in the Irish rebellion, he was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment in Van Diemen’s Land, but made his escape in 1852. James, who was captured in the Canadian rebellion, had escaped the island seven years before Meagher arrived, but he had learned about Meagher through newspaper reports. Just two years after his conversation with the general, James was shocked to read about his tragic death: “…suddenly in the summer of 1867, after beating the odds time and again on three different continents, Thomas Francis Meagher fell off a riverboat (at Fort Benton) and drowned in the Missouri River at age 44. His body was never found.”(10)

________________________

- Wheeler, p. 331.

- Duncan, Elaine, “An Adventurous Pioneer,” 1926. (Elaine Ducan, great granddaughter of James Gammell, wrote this article when she was sixteen years old.)

- Montana Historical Society, “The Pioneers”, author unknown.

- Larry Preston, in his 1956 paper on James Gemmell (pp. 17-18), cited an oral tradition passed down by family members. As the story goes, James’ daughter Jeanette accompanied him on the trading expedition in spring 1863 from Salt Lake to Ruby Valley, Alder Gulch, and the Yellowstone region. There are many questionable aspects to the story; therefore it is not included here. To name just two, Jeanette would have been just eleven years old at the time…very young for such a dangerous trip. Also, James spent the winter in camp with his mill crew, before returning to Salt Lake Valley.

- Montana Historical Society, “The Pioneers”, author unknown.

- Walker, Joseph C., pp. 40-41, 64-65.

- Walker, Joseph C. pp. 40-42, 64-66. See also “The Pioneers”, author unknown.

- Walker, Joseph C., p.65.

- Walker, Joseph C., pp. 65-66.

- http://www.ricksteves.com/plan/destinations/ireland/meagher.htm General Meagher’s statue still stands in front of the state capitol building in Helena.